March 5, 2023 –

Summary

- Inflationary fears have reasserted themselves among investors in the last month.

- This has led to an upward revision to the Federal Reserve’s target rate trajectory, increased Treasury yields, and lower stock prices.

- The data supports a more sanguine view of inflation, as headline inflation, goods, and commodity price pressures remain tame.

- An important tail risk is a potential feedback loop between strong economic growth and services inflation.

- A balanced position in stocks and credit-safe (Treasury and investment grade) bonds feels like the optimal investor response.

Setting the stage

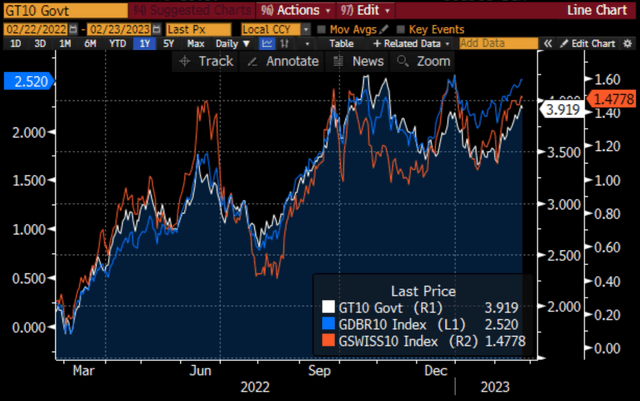

The sharp rise in interest rates in the U.S. and globally has been the dominant theme in markets over the past month. The next chart shows that U.S. 10-year Treasury yields increased by roughly 50 basis points since their January lows. German and Swiss 10-year rates behaved similarly.

Global 10-year rates (Bloomberg)

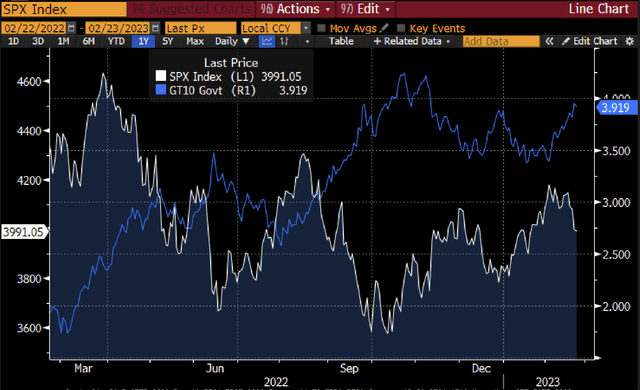

As interest rates rise, other securities begin to look less attractive. A 1.6% dividend yield on the S&P 500 may entice investors when 10-year rates are at 3.4%. But when 10-year rates are pushing 4%, that 1.6% dividend yield may no longer cut it. Most fair-value stock models would suggest that stock prices should fall as yields go up. And so it has been this time around, with the S&P 500 index suffering declines since its early-February highs.

The S&P 500 index and 10-year Treasury yields (Bloomberg)

Economists would describe this as a discount rate driven sell-off. Stock prices have fallen not because medium- or long-term earnings expectations have declined, but because discount rates (i.e., interest rates plus a premium for owning risk assets) have risen. The thing about discount rate driven market declines is that expected returns are higher after the sell-off than they were before. (The same cannot be said about sell-offs that occur due to drops in earnings expectations).

That’s all well and good, but if rates keep on rising, risk assets, stocks included, may continue to sell off. So what to make of this interest rate-driven sell-off?

Why are interest rates going up?

In a nutshell, rates are going up because inflation fears are rising. The precipitating event here was the February 3rd jobs report. Nonfarm payrolls came in at 517,000 which was stunningly above the consensus 189,000 estimate. Investors revised upward their projections for economic growth. Talk turned from a narrative of a soft landing to one of no-landing (i.e., no recession). No recession means a stronger-for-longer jobs market and rising inflation via the Phillips curve dynamic. This means a more hawkish Fed (and more hawkish central banks globally), a higher path for interest rates, and lower risky asset prices via the discount rate channel we described above.

Are the inflationary fears justified?

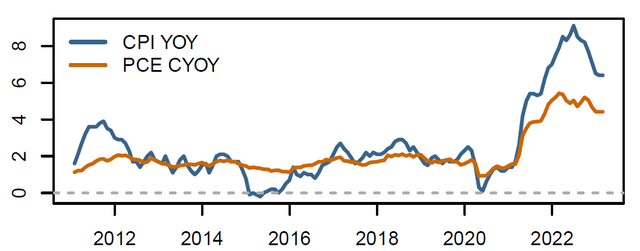

To better understand whether elevated inflation fears are warranted, consider what is happening to inflation in the U.S. After the post-COVID price spikes, exacerbated by supply-chain and Ukraine war disruptions, inflation in the U.S. has started to trend down, as the tightening that the Fed introduced into the system began to cool off economic growth and the red-hot housing market (the most recent jobs report notwithstanding).

U.S. inflation measures (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

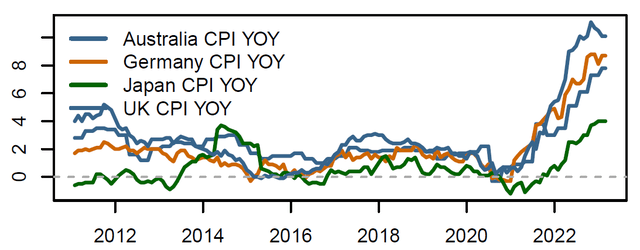

The U.S. is ahead of other countries in terms of controlling headline inflation, but inflation has started to slow globally as well.

International inflation (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

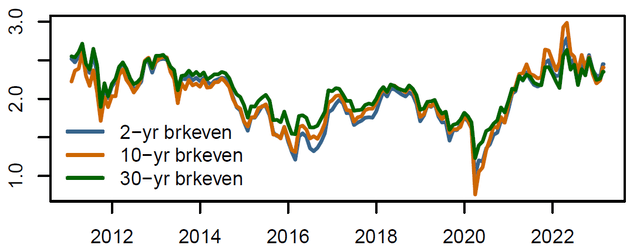

Breakevens are defined as the difference between nominal Treasury yields and the yields of comparable maturity TIPS (Treasury inflation-protected securities), which represent the level of real (i.e., inflation adjusted) interest rates. Breakevens reflect the market’s expectation for future inflation, as well as a risk premium associated with owning nominal bonds. Despite the rise in inflation concerns in the popular press, investors remain relatively sanguine as breakevens have not increased in any meaningful way so far this year.

Treasury breakeven rates (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

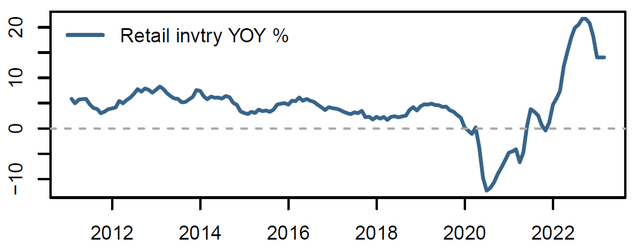

Any concern about goods inflation can also be put to rest, as retail inventories remain high, suggesting retailers can’t move the inventory already sitting on the shelves.

Retail inventories year-over-year growth (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

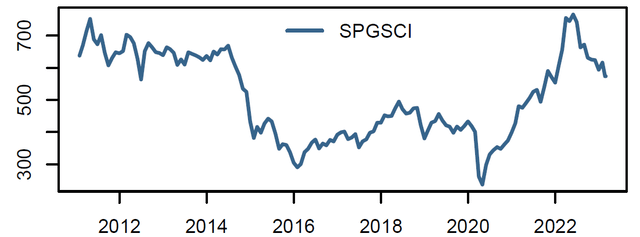

And while commodity inflation remains a distinct possibility from a risk-management point of view, actual commodity prices have been steadily trending down over the last few months, suggesting additional easing in inflationary pressures.

S&P Goldman Sachs commodity index (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

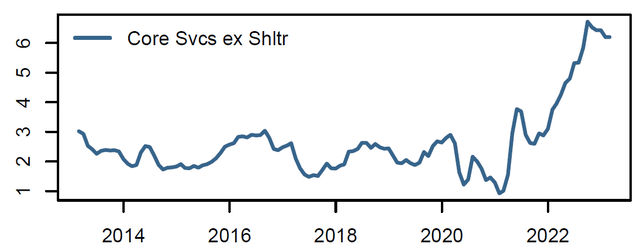

If realized inflation, breakevens, retail inventories, and commodity prices are all pointing towards moderating inflation pressures, then what is the source of the market’s inflationary angst? The answer lies in the services sector, as inflation hawks point to labor-intensive services as the current engine of price pressures. Looking at the data shows that service inflation, while also trending down from its 2022 highs, has remained more stubborn than the more goods-heavy inflation measures.

Services inflation ex shelter (QuantStreet, Bloomberg)

Takeaways for investors

Increased inflationary angst appears to be the main driver of the recent sell-off in fixed income securities and in risk assets. However the data, some of it backward- and some of it forward-looking, points towards an ameliorating inflationary backdrop. The main worry now is a hot jobs market and stubborn services inflation feeding into consumers’ long-term inflation expectations. Our bet is that the Fed and other global central banks will ultimately win this fight — and breakevens seem to agree with our assessment — but there is certainly scope for bumps along the way.

The bumps are likely to favor a position in government or high-quality corporate bonds, as a decline in growth expectations is likely to feed into lower interest rates and higher prices of credit-safe bonds, while reduced earnings expectations and increased fears of default will augur poorly for stocks and high-yield bonds. On the other hand, should services inflation fears prove overblown — which feels like the base case to us — the associated drop in rates will be accompanied by sanguine earnings expectations, which could lead to a sharp increase in stock prices.

Our two cents are betting on the latter scenario, but the risks of the former cannot be overlooked. This favors a relatively balanced position in stocks and bonds, which is a recipe that (outside of 2022) has generally served investors well. As always, the exact stock/bond balance must reflect investors’ particular risk appetites and liquidity needs.