January 25, 2026 —

Dollar positives include relatively high US interest rates and robust growth. But dollar negatives are building. The political will for a stronger dollar isn’t there and valuations aren’t helping.

Backdrop

Since QuantStreet launched in December 2021, we’ve had a bullish view on US assets and on the dollar. The former is still true. We are believers in the AI revolution and don’t buy the AI bubble argument. But the latter is starting to change. Based on the behavior of the US stock market and the dollar after last year’s tariff selloff, this view seems to be the consensus.

Let’s first take a look at the dollar positives.

Positives

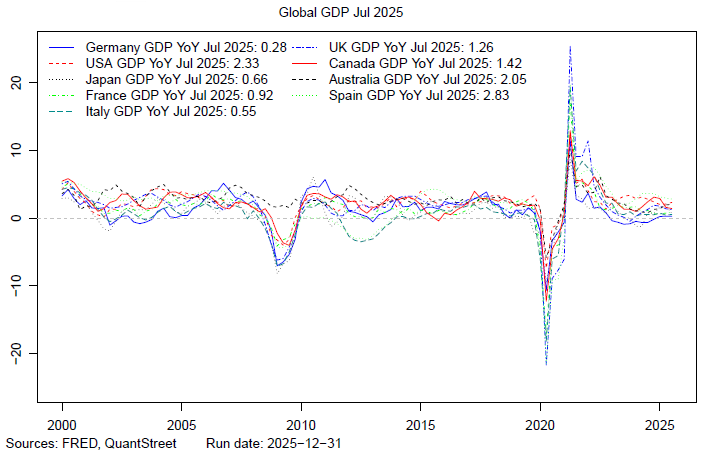

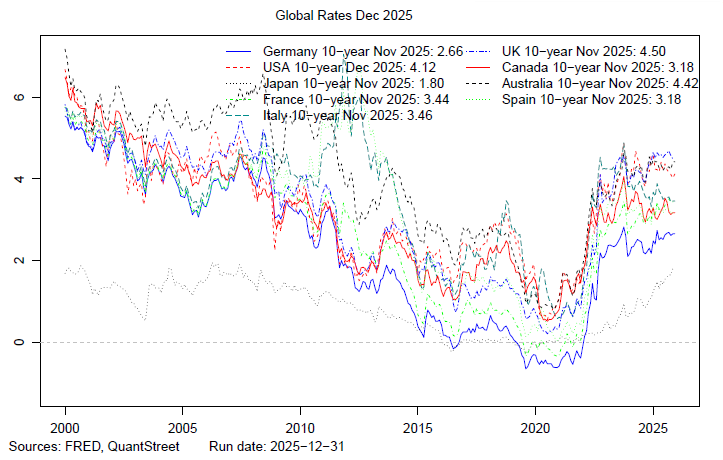

US growth exceeds that of the rest of the world. This raises US interest rates and attracts global capital, both of which are dollar positive.

Second, US rates are high relative to other countries.

By swapping out of 10-year US Treasuries into 10-year Italian or French government bonds, investors give up over 0.60% in yield, and arguably switch into lower quality credits to boot. The terms of that swap also make the dollar attractive.

But the negatives are starting to pile up.

Politics

The aha moment for me came after reading the WSJ article from Dec 27, 2025 titled “Trump wants a weaker dollar. Some Chinese say he has a point.” To quote from the article:

“You make a helluva lot more money with a weaker dollar,” the president said in July. When the dollar is strong, “you don’t do any tourism, you can’t sell tractors, you can’t sell trucks, you can’t sell anything.”

Nothing new here. President Trump is a mercantilist at heart and wants the US to have balanced trade with the rest of the world. Though it will come with many knock-on effects, one way to unwind our trade deficit is to have dollar depreciation: foreign goods become more expensive and US exports become cheaper.

The article continues:

Liu Shijin, a longtime top economic adviser to the (Chinese) government, said in a speech this month that the U.K. and U.S. also started out as primarily manufacturing powers with puny currencies but eventually matured beyond that stage.

Liu cast an envious eye toward Trump’s ability to make the world shudder over U.S. tariffs, which he said was the result of dollar-wielding American consumers’ buying power. Liu said that the whip hand rightfully belongs to China, since its population gives it a potential consumer market “far exceeding the U.S.”

“We should aim for a basic balance between imports and exports” and push for a strong, globally used currency, Liu said.

If influential thinkers in China are pushing for a stronger yuan and weaker dollar, a large part of the trade mechanism supporting dollar weakness disappears. I don’t think a strong yuan represents the CCP’s official policy, but markets will move long before the official policy does.

Add to this President Trump’s desire for lower rates and his search for a new Fed chair who will deliver them—which would diminish both the dollar’s carry advantage and the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility—and the political ingredients for dollar weakness are in place.

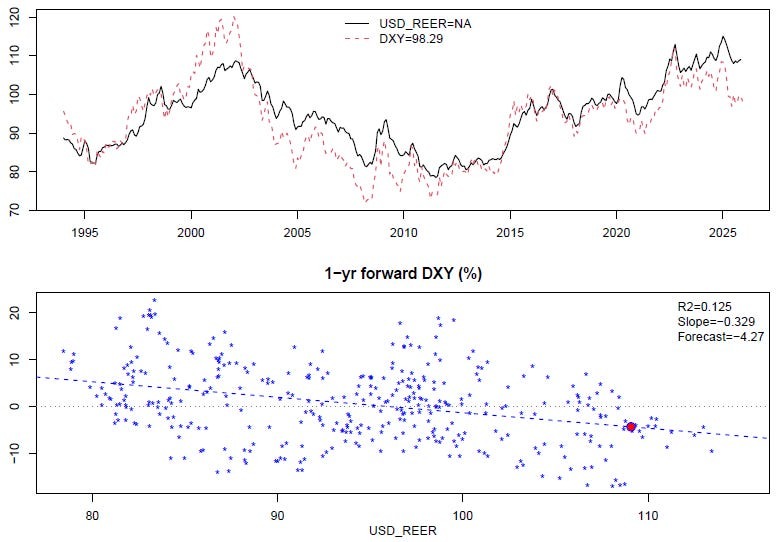

Real effective exchange rate

Another pillar supporting the weaker dollar thesis is the dollar’s high real effective exchange rate. Consider a consumption basket of US goods, with a price of $P. Say the price of one dollar in terms of euros is €S (right now, the euro price of a dollar is around €0.85) and the price of a similar consumption bundle in Europe is €PE. The real dollar-euro exchange rate is then

dollar/euro real exchange rate = S x P / PE.

This is the ratio of the euro price of buying the consumption bundle in the US to the euro price of buying the consumption bundle in Europe. The higher this is, the more “expensive” is the dollar. A trade-weighted average of this ratio across all global currencies yields the dollar’s real effective exchange rate (REER).

Expensive currencies tend to depreciate in nominal terms, though this is not always the case (e.g., the yen has been “cheap” on a REER basis for a long time and continues to get “cheaper”). This happens because countries with expensive currencies run trade deficits (since foreign stuff is cheaper than domestic stuff), so their currencies go out into the world to buy other countries’ goods. As the global supply of the currency grows, assuming demand stays fixed, prices adjust downward.

The next chart shows the dollar’s REER (in black) and nominal effective exchange rate (NEER, red, dashed line). The dollar’s REER is close to an all-time high, despite the dollar’s nearly 10% sell-off in 2025. The bottom panel of the chart plots the one-year ahead change in the dollar’s nominal exchange rate against the dollar’s current REER. For every point above its steady-state level (of around 96, where the regression fit line crosses the x-axis), the dollar tends to depreciate by 0.329 points over the next year. This point has been made in the academic literature, e.g., Cashin and McDermott (2004), so the result stands up to statistical scrutiny.

Sources: QuantStreet, BIS, FRED

Given its current valuation level, the dollar is forecasted to depreciate by 4.27% over the next year, and by twice that amount over the next two years.

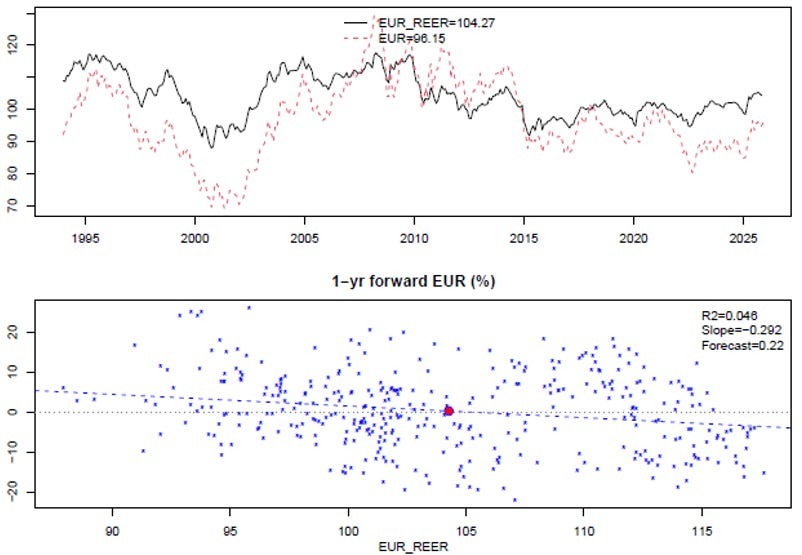

The next figure applies the same analysis to the euro. The euro’s valuation appears neutral based on its historical REER, and the euro forecasted change for the year ahead is close to zero.

Sources: QuantStreet, BIS, FRED

Flows

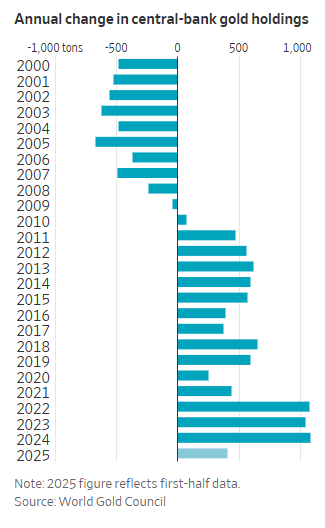

An unintended consequence of sanctioning foreign countries by freezing their dollar assets has been to push them into other stores of value. The Jan 23, 2026 WSJ article “Five reasons gold is surging toward $5,000 an ounce,” carries the following chart using data from the World Gold Council which shows extreme buying of gold by global central banks.

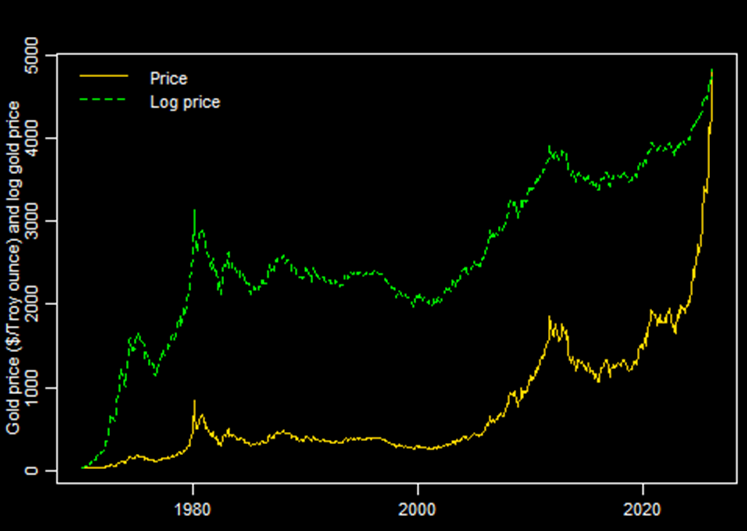

These central bank flows into gold have been augmented with investor flows into exchange traded funds like GLD and IAU. Together with gold’s inelastic supply, this has pushed up the price of gold to near $5,000 per troy ounce, a dramatic appreciation both in nominal and inflation-adjusted terms.

The interpretations of the above chart vary. One is that gold is in a bubble. After such an extreme price run-up—both in speed and magnitude—it’s hard to definitively rule out a bit of froth in the gold price. But the other interpretation is that, while the dollar and Treasuries still represent the majority of global reserve holdings, the dollar’s position as the sole global reserve currency is slowly deteriorating. This shift to other stores of values is most readily seen in assets whose supply cannot be adjusted in the short-run, like gold.

Not helping matters is the general frustration among America’s allies with the Trump administration’s foreign policy. For example, while I think the Greenland situation will be resolved to the satisfaction of both the Trump administration and our European allies, the way it has been handled over the last week has diminished the desire of European to hold US assets, with some going so far as to call for a concerted effort to reduce exposures. I don’t think this is a plausible path forward (neither does the FT’s Robin Wiggleworth), but even a marginal move in this direction will continue to chip away at the dollar’s reserve currency status. This FT article explains further.

Portfolio implications

To summarize the dollar thesis, here are the two positive:

-

US interest rates are high relative to other developed market economies; and

-

US economic growth is relatively strong.

The negatives are:

-

The Trump administration wants a weaker dollar;

-

High dollar valuations forecast future nominal depreciation;

-

Political interference with the Fed is dollar negative;

-

The signal from the gold market is bad;

-

Widespread frustration with the Trump administration’s foreign policy.

Whatever one thinks of the prospects of US versus international stocks, a 4.27% annual headwind will be difficult for US assets to overcome. Based on QuantStreet’s analysis of long-term valuations trends, our forecast for US and international stock returns are close to each other. Adding in the dollar headwind for US assets, and conversely its tailwind for international ones, suggests investors with light international allocations should rethink their portfolio positions. If you’d like our advice on how to do that, please reach out.

Working with QuantStreet

QuantStreet is a registered investment advisor. It offers financial planning, separately managed accounts, model portfolios and portfolio analytics, as well as consulting services. The firm’s approach is systematic, data-driven, and shaped by years of investing experience. To work with or learn more about QuantStreet, contact us at hello@quantstreetcapital.com or sign up for our email list.