7/17/2025 —

Many portfolios consist of highly appreciated, concentrated positions. Investors are hesitant to rebalance these portfolios to avoid paying capital gains taxes. Such hesitancy if often unwarranted.

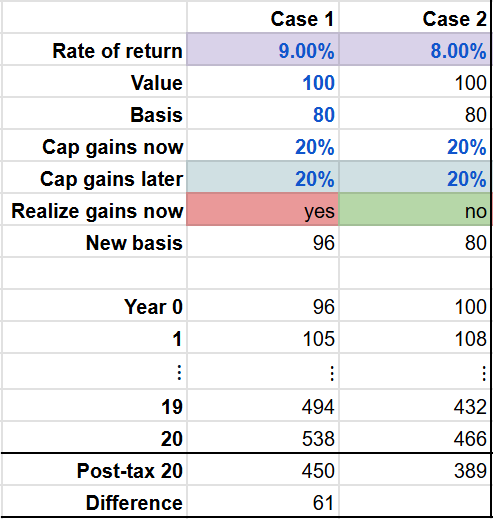

Consider an investor with an existing portfolio worth $100. The cost basis of the portfolio is $80. The portfolio consists of high cost mutual funds and ETFs, as well as several legacy stock positions which are historically poor performers.1 The investor estimates that the current portfolio will generate an 8% annual return over her 20-year planning horizon. At the same time, the investor believes that by rebalancing the portfolio, she can achieve a 9% annual return over the same time period. If she rebalances, she will have to pay a current capital gains tax of 20%, i.e., we assume all capital gains are long-term and there is no state capital gains tax. Please note that the 8% and 9% returns are purely illustrative assumptions to demonstrate the tax tradeoff and are not forecasts of actual portfolio performance.

If the investor does nothing today (Case 2), she will earn an 8% return for the next 20 years, which will generate $466 in the account at the end of year 20. At this point, we assume the investor liquidates the entire portfolio at a future capital gains tax rate of 20%. Relative to an $80 cost basis, this leave $389 in the account at the end of year 20 after taxes have been paid.

The alternative for the investor is to sell the entire portfolio today (in reality, the investor may rebalance only a portion of the portfolio), pay a $4 capital gains tax ($20 gain x 20% tax rate), and reinvest the proceeds from the sale into the new, higher returning portfolio. The cost basis of the new portfolio will be $96. This then gets invested at 9% for the next 20 years, generating a pre-tax value in year 20 of $538. After paying a 20% capital gains tax relative to a $96 cost basis, the post-tax value in the account is $450.

The portfolio rebalance, despite its immediate capital gains cost, generates $61 additional post-tax dollars in the portfolio in year 20. If the investor was hesitant to do this rebalance, she should not have been.

Analysis

There are two factors at play. First, how much does the investor pay in taxes now if she sells? The cost of paying higher taxes now is that the money paid in taxes cannot earn interest for the next 20 years in the investment account. (A benefit of rebalancing is that the portfolio’s cost basis goes up, which means lower taxes in the future.) Second, how much extra return does she earn from rebalancing the portfolio today? If the extra anticipated return is sufficiently high, it outweighs the return drag caused by paying taxes earlier.

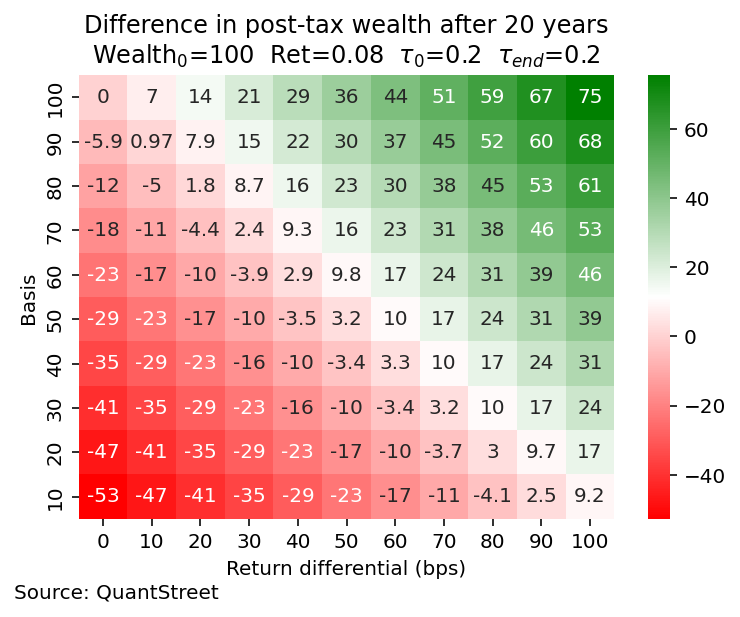

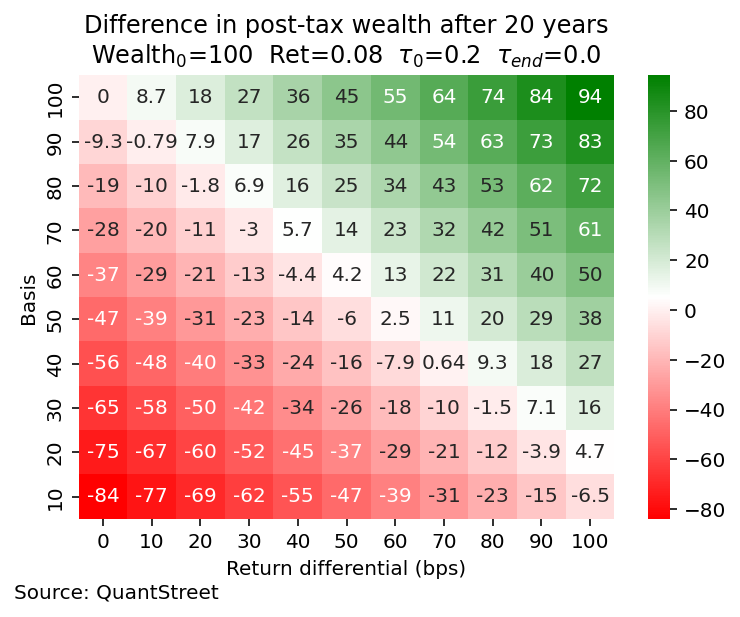

While this was the case in the above example, it is not always so. The next table shows a scenario analysis which varies the portfolio cost basis (y-axis) and the anticipated return gain from rebalancing (x-axis, in basis points). The scenario just analyzed, which generates a $61 gain from rebalancing, is shown in the cell labeled 80 (cost basis) and 100 (annual basis point gain from rebalancing).

But the gains from rebalancing are not always positive. The lower the cost basis, the higher the drag from paying taxes now and foregoing the returns earned on the amount paid in taxes. The lower the anticipated future return differential, the less offset there is to paying taxes earlier. For example, if a $100 portfolio has a cost basis of $50 and the anticipated return gain from rebalancing is only 30 basis points per year (0.3%), then the investor loses $10 in the year 20 post-tax portfolio value from rebalancing today.

As the above scenario analysis shows, if the anticipated return gain is close to one percent per year (100 basis points)—as would often happen from moving from high fee to low fee mutual funds—then almost regardless of the portfolio’s cost basis, the investor is better off rebalancing into the lower fee funds immediately, if her planning horizon is 20 years out.

Impact of step-up cost basis

In many cases, when assets go to loved ones after someone’s passing, they are subject to a step up in cost basis to the market prices prevailing at the time of the inheritance. This is typically advantageous because the cost basis is usually considerably lower than the market value of the inheritance. Depending on the current cost basis of the portfolio, this step-up feature can either advantage or disadvantage the rebalance-now scenario. When the current cost basis is relatively high compared to the portfolio’s market value, a step-up basis at inheritance can make the rebalancing option look more attractive.

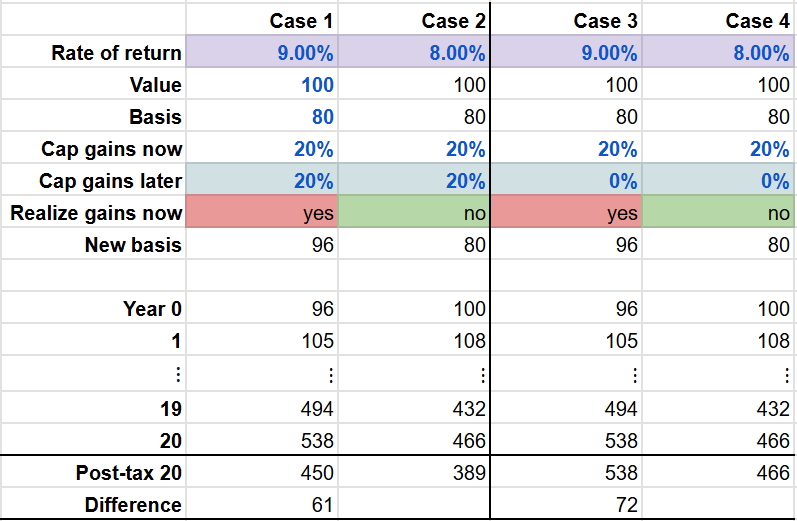

This is what happens in Cases 3 and 4 below. This scenario is the same as Cases 1 and 2, but we now assume that the capital gains tax rate in 20 years is zero (due to the step up in basis). The post-tax value in Cases 3 and 4 is the same as the pre-tax value, and the edge from an early rebalance increases from $61 to $72.

However, a step-up basis can also make the rebalancing less attractive in cases where the current tax basis is low relative to the market value of the assets. In such cases, illustrated in the example below, the benefit of never paying capital gains on current assets (with high unrealized gains) outweighs the benefit of higher anticipated returns, even over the 20 year life of the investment.

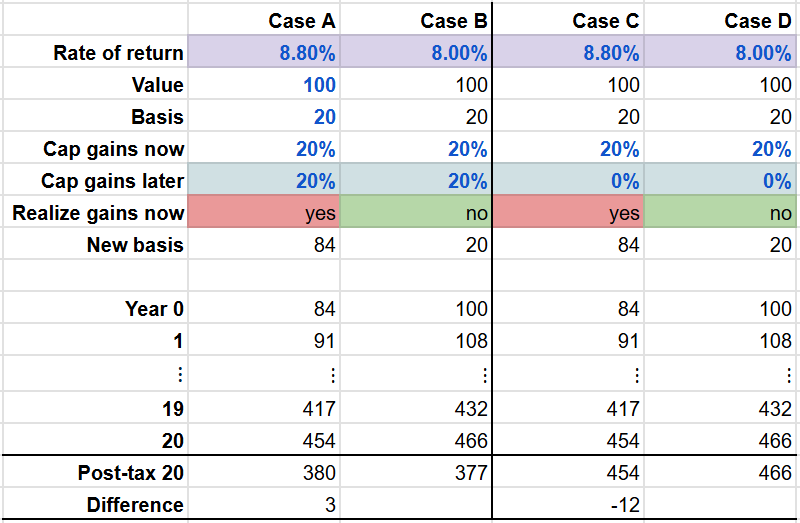

Cases A and B below show the analysis with a very low cost basis portfolio ($20 cost basis per $100 of market value) with a 20% capital gains tax rate in year 20 and a 0.8% annual return differential from rebalancing. The rebalancing option in this scenario generates a benefit of only $3 because the foregone interest from the high initial capital gains tax payment is sizable. In fact, the pre-tax year 20 value of the rebalancing option (Case A) is lower than the pre-tax value of the no-rebalance option (Case B), but because of the latter’s extremely low cost basis, the future capital gains tax is very punitive, giving the rebalancing option a higher post-tax account value.

Cases C and D show the same scenario, but with a step-up basis and thus an effective future capital gains tax rate of 0%. This generates a very large benefit for the no-rebalance scenario (Case D) because the very low $20 cost basis of the portfolio does not generate a large future tax bill. In this case, not rebalancing yields a $12 benefit over the rebalance option.

The next table performs a scenario analysis by varying the current portfolio cost basis (y-axis) and anticipated return differential (x-axis), while assuming a step-up basis upon inheritance, and thus an effective future capital gains tax rate of 0%.

The rebalancing option is still almost always beneficial when the anticipated return differential is close to 1% (100 basis points) per year, even with a step-up cost basis. The benefit of rebalancing is now lower for the low cost basis portfolios (because having zero capital gains tax rates in the future is so beneficial for portfolios with a low future cost basis, i.e., those the result from not rebalancing today), but it is sometimes higher for today’s high cost basis portfolios (because all of the anticipated higher pre-tax account value after rebalancing stays in the account, and does not have to get paid out in taxes).

Portfolio level analysis

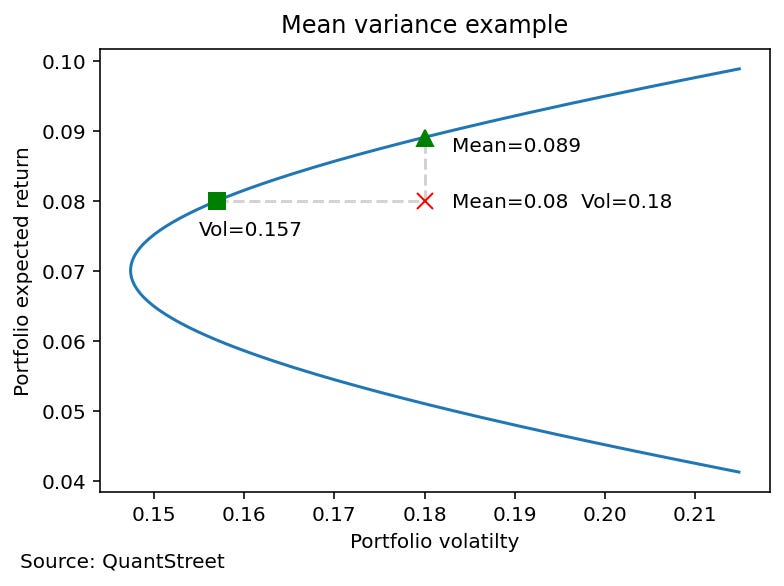

The above analysis can be nicely explained in the context of modern portfolio theory. In the chart below, the blue curve—known as the efficient frontier—shows, for every level of expected return (y-axis), the minimum volatility (x-axis) at which that expected return can be achieved.

The investor’s high unrealized gain portfolio can be thought of as the red X in the figure. It has an anticipated return of 8% per year and a return volatility (which measures how much the portfolio can change in value in a given year) of 18%. This portfolio is not optimal. For example, the investor would be better off rebalancing to the green triangle because that portfolio has the same volatility as the red X (18%), but a higher anticipated return (8.9%). The 0.9% gain in annual anticipated return can be used in the above scenario analysis to determine the dollar benefit of paying capital gains taxes now and rebalancing.

Another portfolio that is preferable to the red X is the green square. It has the same anticipated return (8%) but a much lower volatility (15.7% per year). (In fact, any portfolio in the quasi-triangle demarcated by the dashed lines and the blue curve is better than the red X.) Using the tools of modern portfolio theory, we can translate this 2.3% per year volatility differential into an implied difference in anticipated returns of around 1.55%.2 Again, an inspection of the above scenario analysis tables shows that with this anticipated return differential, rebalancing immediately is almost always beneficial (in fact, the tables only show return differential up to 1%).

Caveats and conclusion

Several real-world considerations may impact the conclusions:

-

In the first part of the analysis, we ignored uncertainty. Assuming a deterministic annual return of 8% or 9%, while simplifying the analysis, may overstate the benefit of immediately rebalancing by not considering possible adverse return paths. This can be evaluated using Monte Carlo studies, but is beyond the scope of the present article.

-

Related to the above concern, we are not explicitly considering that portfolios consist of multiple securities with correlated return streams and different risk characteristics (like the propensity to experience large drawdowns), which may not be well represented by modeling the portfolio as a single return stream. Again, Monte Carlo studies can be used to analyze this scenario.

-

We did not consider 351 exchanges, a new type of financial structure which may allow for efficient diversification (e.g., moving from the red X to the green triangle) without paying any capital gains taxes in the short term.

-

The tax code may change in the future. For example, capital gains tax rates may be higher or lower, or there may be a state capital gains tax in currently exempt states. Tax code changes can increase or decrease the anticipated benefit of an immediate portfolio rebalance.

These, and potentially other, considerations impact the benefit of portfolio rebalancing in the presence of capital gains taxes. But when the anticipated gain in returns is of the order of 1% per year or more, or the drop in portfolio volatility is meaningful, and the planning horizon is in the 20+ year range, it often makes sense for investors to rebalance legacy portfolios. This is true even if doing so generates capital gains taxes in the short run.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not investment advice. Please consult with a tax professional and your investment advisor before deciding on a portfolio rebalance or making other investment decisions.

Working with QuantStreet

QuantStreet is a registered investment advisor. It offers financial planning, separately managed accounts, model portfolios and portfolio analytics, as well as consulting services. The firm’s approach is systematic, data-driven, and shaped by years of investing experience. To work with or learn more about QuantStreet, contact us at hello@quantstreetcapital.com or sign up for our email list.

Assume a mean-variance utility, where U = E[return] – 0.5*A*portfolio variance. This can be thought of at the portfolio’s expected return adjusted for its risk. A representative value of A, known as the risk aversion coefficient, is 4. The utility associated with the red X is 0.08-2*0.18^2=0.0152. The utility associated with the green square is 0.08-2*0.157^2=0.0307. The difference between these—which can be interpreted as an anticipated risk-adjusted return—is 0.0155 or 1.55% per year.